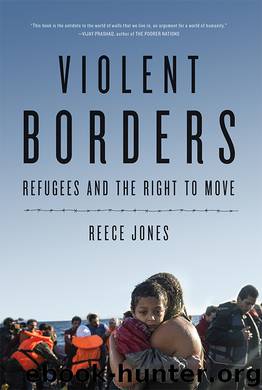

Violent Borders: Refugees and the Right to Move by Reece Jones

Author:Reece Jones

Language: eng

Format: epub, mobi

Publisher: Verso

The enclosure of the ocean

At the turn of the twentieth century, the oceans were one of the last bastions of free movement and unclaimed resources on earth. Through the end of World War II, most states only claimed territorial seas stretching three nautical miles off their coasts. These zones were based on the “cannon-shot rule,” corresponding to the area that could be defended by armaments on shore in the seventeenth century. Beyond that zone, more than 95 percent of the surface area of the oceans and 70 percent of the surface of the earth was open to fishing and free movement by any ships. However, in the twentieth century, states around the world aggressively expanded their control of ocean spaces in order to claim the resources and wealth that lay beneath the seafloor.58

Humans have used the seas for fishing and movement for millennia. The Polynesians traveled throughout the Pacific Ocean using the stars to navigate.59 The Indian Ocean has a rich history of trade between Africa and South Asia.60 The Mediterranean served as the transportation link for the Greek, Roman, and Phoenician civilizations.61 During the period of European colonization, the high seas were important spaces for the transportation of goods around the world and for the control of distant lands. In the sixteenth century, as more vessels were making long-distance voyages, England, the Netherlands, Portugal, and Spain challenged each other for the ability to control the seas. The key positions on the right of free movement on the high seas were laid out by jurists in the Netherlands and England. Hugo Grotius, an influential Dutch jurist who also wrote significant texts about private property, made the case for the Dutch position in his Mare Liberum (1609), which argued that the seas are a common space for the shared use of all states for trading purposes. The English monarchy did not accept this position, primarily because they wanted to control fishing grounds near their coasts, which were being used at the time by boats from the Netherlands as well as Scandinavia. English legal scholar John Selden’s Mare Clausum (1635) was a rejoinder to Grotius and argued that states could effectively treat coastal seas as their territories. By the early eighteenth century, the profits from long-distance trade outweighed the need for exclusive fishing grounds. All of the European powers accepted the notion of free movement on the high seas, with a limited three nautical miles off the coast as the territorial sea of a state.

This general agreement of three nautical miles held until the end of World War II. The realization that there were many resources in the ocean and under the seafloor that could be made productive with new extraction technologies has driven the changing political geography of the ocean.62 In addition to fisheries, the demand for fossil fuels transformed states’ claims to resources in the oceans as massive oil and gas reserves were discovered under coastal waters and on continental shelves. The United States was the first to challenge the status quo of freedom of movement on the high seas.

Download

Violent Borders: Refugees and the Right to Move by Reece Jones.mobi

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Anthropology | Archaeology |

| Philosophy | Politics & Government |

| Social Sciences | Sociology |

| Women's Studies |

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(19097)

The Social Justice Warrior Handbook by Lisa De Pasquale(12193)

Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher(8915)

This Is How You Lose Her by Junot Diaz(6891)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6283)

Zero to One by Peter Thiel(5805)

Beartown by Fredrik Backman(5763)

The Myth of the Strong Leader by Archie Brown(5511)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5452)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(5221)

Promise Me, Dad by Joe Biden(5155)

Stone's Rules by Roger Stone(5089)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4965)

100 Deadly Skills by Clint Emerson(4929)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4792)

Secrecy World by Jake Bernstein(4755)

The David Icke Guide to the Global Conspiracy (and how to end it) by David Icke(4721)

The Farm by Tom Rob Smith(4516)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4492)